How a statewide canopy comeback can protect water, cool neighborhoods, restore wildlife, and strengthen communities, one large planting and one yard at a time.

From Forests to Lawns: How Delaware’s Landscape Has Changed

Before European settlement, Delaware’s uplands and bottomlands were largely continuous forests. Old, diverse stands covered the hills, and swamp forests and wooded wetlands braided through lowlands and tidal areas. Indigenous stewardship used careful fire and selective clearing but left the overall canopy intact. Forests filtered water through soils, kept microclimates cool and humid, and supported a full array of wildlife that had evolved in those conditions

Colonial clearing changed the system quickly. Forests were felled for agriculture and timber. Streams were dammed and redirected. Wetlands were ditched and drained. By the early twentieth century, the state had lost roughly three quarters of its original forest canopy. The stands that remained were mostly young secondary forests that lacked the structural variety of old growth. Creek channels had shifted, hydrology had been altered, and nutrient and sediment pollution had become a chronic threat to water quality.

A second transformation followed the Second World War. Farmland and remaining woodlots gave way to subdivisions, shopping centers, and new roads. Turfgrass lawns became the cultural default. In Delaware’s suburbs today, the typical yard is a wide, mowed lawn with a few isolated ornamentals. Lawns require mowing, fertilizer, and irrigation, but they do not filter water like a forest floor, they do not hold soil with deep, varied roots, and they do not feed native food webs. What looks green from the curb often functions as a biological desert.

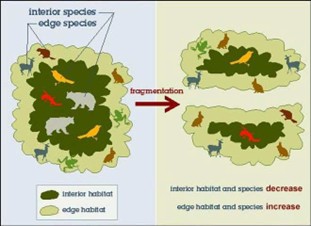

Fragmentation compounded the loss. Where continuous forests once stretched for miles, many small parcels are now separated by roads and development. Sun, wind, heat, and invasive plants penetrate deep into these small patches. Predators and nest parasites thrive along edges. Many forest-dependent species depend on interior habitat, areas far from edges to nest successfully and maintain populations. When most of the remaining woods are small and edged, interior conditions become rare, and wildlife struggles even when the canopy looks “present” on a map.

This is the legacy the state inherits: a landscape that still has trees, but not enough large, connected, native forests to deliver the services that people and wildlife need. It is also the starting point for recovery. Delaware can rebuild canopy strategically, on public and private land, at large sites and one yard at a time, so that forests again perform as the natural infrastructure they are.

The Delaware Canopy Today: What We Have Left

Delaware has roughly three hundred and fifty-nine thousand acres of forest, or about twenty-eight percent of the land area. The majority, nearly four out of five acres, are privately owned by families, farmers, and other landowners. Public ownership accounts for just under one fifth. Corporate ownership holds a smaller share. That ownership pattern matters because the future of the canopy depends on choices made on private lands as much as decisions made on public lands.

Three state forests, Blackbird, Taber, and Redden, together total just over twenty-one thousand acres. These are working forests that demonstrate how active management can strengthen resilience: thinning overcrowded stands, restoring hydrology, conducting prescribed fire in suitable ecosystems, controlling invasive plants, and replanting with diverse native species. They are also public classrooms where school programs and community groups learn forestry, wildlife ecology, and outdoor skills.

Against that base, several pressures continue. Development and parcelization convert or carve up forests. Invasive insects and diseases, including emerald ash borer, spongy moth, and beech leaf disease, threaten specific species and stand health. Climate stress intensifies heat, storm intensity, and erratic rainfall. Coastal saltwater intrusion harms low-lying forests. Cultural norms continue to favor turfgrass over layered native plantings in towns and suburbs.

These pressures are serious, but they are not a verdict. They frame the work that Delaware is already doing at scale to rebuild canopy and the choices that residents can make to accelerate that work close to home.

When Trees Disappear: The Problems We Face

Water quality suffers. Without the roughness of leaves, twigs, trunks, and forest floors, rainfall hits the ground hard, runs quickly across compacted soils and pavement, and delivers sediment, fertilizers, and other pollutants to streams and bays. Forested buers slow, store, and filter that water. When buers are missing, utilities spend more to treat drinking water, and communities spend more to manage flooding and erosion.

Flooding becomes more frequent and severe. Trees intercept and slow rain, promote infiltration, and stabilize soil. Their root systems literally hold the ground together. When canopy is sparse, stormwater moves rapidly into channels that were not built for sudden volumes. In a low-lying state facing sea-level rise and stronger storms, missing trees turn heavy rain into a costly emergency.

Neighborhoods heat up. Shade is a public health service. Canopy lowers daytime temperatures and helps nights cool. Without trees, urban and suburban neighborhoods heat quickly and cool slowly. Heat burdens fall hardest on places that already have less canopy, on older adults, on infants and children, and on outdoor workers.

Biodiversity erodes. Interior forest birds cannot breed successfully along edges. Amphibians that need shaded, moist leaf litter disappear. Specialist pollinators lose the native host plants they require. As native species decline, invasive plants often fill the gap, benefitting from sunlit edges and disturbed soils.

Costs rise. Energy bills increase as air conditioners run longer. Municipalities spend more on stormwater basins, emergency response, and repairs. Asphalt degrades faster without shade. Heat-related illness and respiratory problems drive health costs higher. Property values and neighborhood stability tend to lag in the places with the least canopy.

All of these problems are real, measurable, and preventable. All of them improve when trees return in the right places and are allowed to mature into layered, native plant communities.

Wildlife on the Edge: Species Struggling Without Forests

Forest interior songbirds such as wood thrushes, scarlet tanagers, ovenbirds, and a suite of warblers require deep interior conditions to nest successfully. In small, edge- dominated patches, nests are easier for predators to find and for cowbirds to parasitize. Food availability also declines when the native trees and shrubs that support caterpillars are missing. Even when these birds still appear during migration, breeding success falls without interior forest.

Raptors, owls, and cavity nesters need mature structure. Broad-limbed trees support nesting platforms for hawks and eagles. Old trees that develop cavities and loose bark provide roosts and nest sites for owls, woodpeckers, small mammals, and bats. When a landscape of quick-growing ornamentals replaces mature natives, this structural habitat disappears.

Amphibians and reptiles depend on the cool, moist microclimates and intact leaf litter that only forests provide. Vernal pools shaded by woods are nurseries for salamanders and frogs. When canopy thins and the ground dries, those pools fill with sediment, warm up, and fail to support amphibian life cycles. Box turtles, black rat snakes, and other species that move between wetlands and uplands need wooded corridors to travel safely.

Mammals and specialist pollinators are tightly bound to native flora. The acorns, nuts, and fruits of native trees feed squirrels, foxes, and countless seed-eating birds. Many bees and butterflies evolved with specific native host plants that grow under native canopies. When those trees and their understory companions are replaced with turf and non-native ornamentals, specialists vanish from the area even if generalist species remain.

Restoring native, layered canopy is the fastest way to bring these animals back. Trees are not just background. They are the framework of the living system.

Planting Power: How Trees Heal Lands and Communities

Tree planting works at two scales that reinforce each other.

Large-scale reforestation and aforestation rebuild forest function across dozens of acres at once. Reforestation restores tree cover where forests previously grew but were removed. Aforestation establishes forests on lands that are currently non-forested but suitable for trees. Strategic large plantings reestablish interior conditions that fragmented patches cannot provide, reconnect woods that have been isolated, restore hydrology on degraded sites, and capture nutrients before they enter streams and bays.

Best practices are simple in principle and disciplined in execution. Plant species must match site hydrology and soil—swamp white oak, river birch, sycamore, black gum, and bald cypress for wet ground and floodplains; white oak, chestnut oak, northern red oak, American beech, tulip poplar, and hickories for uplands; salt-tolerant natives for coastal exposure. Structure matters. Planting for a future layered forest—canopy, understory, shrub, and groundcover—accelerates the return of food webs. In areas with heavy deer pressure, young trees require protective tubes or fencing. Competing vegetation and invasive plants must be controlled during the establishment period. Extended summer droughts require deep, periodic watering until roots run wide and deep.

Individual plantings on private land scale the work across thousands of parcels. Every yard, school, campus, faith community, and business park is a candidate. Replace a lawn strip with a native canopy tree and a ring of native shrubs underneath. Plant a street tree on a hot block to shade pavement and people. Add native trees along a drainage swale, ditch, or stream to filter runoff. Remove a nonnative ornamental that provides little wildlife value and replace it with a native that feeds birds and pollinators.

Layer plantings so that the tree is not surrounded by sterile mulch but by living groundcovers and shrubs that protect soil, support beneficial insects, and reduce maintenance over time.

Large plantings create interior habitat and reconnect broken patches. Small plantings provide stepping- stone habitat and cool the places where people live. Together, they rebuild a connected, durable canopy.

A Win for People: The Economics of Canopy

Energy savings and comfort. Large, well-placed deciduous trees shade walls and roofs in summer and allow low winter sun to warm buildings. Evergreens placed to the north and northwest act as windbreaks that reduce winter heat loss. At the scale of a neighborhood, a canopy that shades sidewalks, streets, and parking areas makes daily life more comfortable and lowers peak electricity demand during heat waves.

Stormwater and flood cost avoidance. Tree canopies are resilient, low-maintenance stormwater systems. Leaves and branches intercept rain. Forest floors absorb and slow water. Roots stabilize soil and increase infiltration. When neighborhoods and towns rebuild canopy, they can reduce the size and cost of engineered drainage and detention structures. Over decades, these avoided costs are substantial.

Public health dividends. Shade and air filtration reduce heat-related illness and respiratory distress. Treed parks and trails support daily exercise and stress reduction. These services improve school performance and workplace outcomes and reduce public and private health expenditures.

Property value and economic vitality. Streets lined with mature trees have higher walk appeal and support stronger local business districts. Residential neighborhoods with visible canopy often see higher property values and lower turnover. A visible canopy is a visible commitment to quality of life.

Keeping forests as forests. In rural areas, sustainable forest management supports small businesses and helps keep land in forest rather than converting it to development. Markets for lower-value wood can pay for thinning and invasive control that improve forest health. While canopy expansion for water, climate, and wildlife is the focus here, the broader forest economy plays a supportive role by making healthy forests economically viable.

A Win for Wildlife: Bringing Back Delaware’s Wild Neighbors

Food webs begin with native leaves. Many birds cannot raise young on seeds alone. They need protein in the form of insects, especially caterpillars, during the nesting season. Caterpillars need native host plants. Oaks, willows, cherries, birches, and poplars support far more caterpillar species than common nonnative ornamentals.When a yard gains a native oak, it becomes a bird nursery that did not exist before.

Shelter and nesting come from structure. Mature trees offer cavities, branch platforms, textured bark, and vertical layers that wildlife needs. An underplanted tree becomes a vertical habitat when native shrubs and groundcovers are added at its base. Brush piles, snags, and leaf litter further increase shelter and foraging.

Movement resumes when patches connect. A single tree can be a perch, a shade source, and a seed source. A corridor of yards that replace lawn with trees and shrubs becomes a safe route for birds and pollinators to move through developed areas. When neighboring blocks do this together, the cumulative efect begins to resemble the function of a preserve.

The Tree for Every Delawarean Initiative: A Million-Tree Framework

How the Initiative operates.

Funding and grants support a wide range of projects. Municipalities and counties add street and park trees to reduce heat and manage stormwater. Conservation districts and landowners reforest or a forest acres that connect habitat and protect water. Schools and nonprofits plant on campuses and in neighborhoods. Technical guidance helps participants choose the right native species for Delaware’s soils and hydrology, site trees to avoid future conflicts with overhead and underground utilities, and plant in ways that maximize survival. Tracking and transparency are built in. A statewide tracker records trees planted by projects and by individual residents, shows where canopy is growing, and highlights where future work is needed. Education and equity are central. Community tree giveaways pair free native trees with planting and care instruction, and urban plantings prioritize neighborhoods with high heat and low canopy.

What the Initiative is achieving.

The statewide push to add one million trees has demonstrated that Delaware can deliver canopy at scale while improving equity and water quality. Large plantings at institutional and farm sites establish interior habitat and reduce nutrient and sediment run of to sensitive waters. Urban and community projects add thousands of street and park trees that cool sidewalks and playgrounds. Pilot tree giveaways place native trees directly into the hands of residents, complete with instructions and a simple way to record their plantings so that every effort counts.

Why the Initiative is different.

The Initiative is not just about numbers. It is a framework that makes sure each planting contributes to a connected, native, durable canopy. It aligns with climate planning, watershed goals, forest health strategies, and wildlife recovery. It empowers residents to act and recognizes that many small actions add up when they are coordinated and tracked. It builds the habit of canopy care into the culture of towns, schools, and neighborhoods.

From Backyards to a National Park at Home

Homegrown National Park is a national movement built around a simple proposition: conservation must happen where people live. The steps are direct. Shrink lawn.

Plant native trees and plants. Remove invasive plants. Make a home for wildlife by providing food, water, shelter, and nesting sites. Then log the work on a national map to make the collective impact visible.

This mission aligns naturally with the Tree for Every Delawarean Initiative. The statewide Initiative provides program structure, funding, technical guidance, and a tree tracker. Homegrown National Park offers a homeowner playbook and a culture shift that makes it normal and desirable to replace lawn with living landscapes. When residents follow Homegrown National Park guidance, they make better selections, plant more successfully, and maintain young trees through the most vulnerable years. When they add their trees to the statewide tracker and to the national map, they can see their efforts as part of something larger.

The result is a feedback loop. Grants and community projects add visible canopy to streets, parks, campuses, and larger parcels. Homeowners build living landscapes around those anchors. The map shows the pattern growing. Neighbors copy what works. Schools teach the next generation with hands-on projects. The pattern scales from block to watershed to county. In a state with a high proportion of private ownership, this is how conservation becomes a mass participation project rather than an expert-only activity.

How to Plant a Tree That Thrives in Delaware

Choose native species that fit the place. Match trees to site hydrology and soil. In wet soils and floodplains, choose river birch, sycamore, swamp white oak, black gum, or bald cypress. In uplands, white oak, chestnut oak, northern red oak, tulip poplar, American beech, and hickories are reliable. Along the coast, seek natives that tolerate wind and some salt. If fruits for wildlife are desired, remember that some species are dioecious and require both male and female plants nearby in order to fruit.

Place trees for energy savings and safety. Plant large deciduous trees to the south and west of buildings for summer shade and winter sun. Use evergreens to the north and northwest as windbreaks that reduce winter heat loss. Keep large-maturing trees well away from overhead power lines. Reserve the space closest to lines for small-maturing species, keep medium trees at a moderate distance, and place large trees beyond the reach of wires. Always locate underground utilities before digging.

Plant correctly and care through establishment.

Set the root flare at or just above ground level. Use the site soil to backfill. Mulch lightly and keep mulch away from the trunk. Water deeply and less frequently rather than shallow and often, especially through the first two growing seasons. Protect young trees from deer where needed. Control invasive vines and shrubs that can overtop or girdle saplings. The most common cause of failure is planting the wrong species in the wrong place or neglecting a tree during its first years.

Layer your plantings.

Underplant trees with native shrubs and groundcovers. Layering shades soil, suppresses weeds, slows runof, and provides food and shelter for wildlife. Over time, fallen leaves and woody debris build living soils that need less work and reward you with healthier trees.

Join the Canopy Comeback

This work is both urgent and achievable. Delaware can protect water, lower flood risk, cool neighborhoods, bring back wildlife, and strengthen communities by rebuilding tree canopy. The pathway is practical and open to everyone.

Plant a native tree in a yard or on a campus. Replace a nonnative ornamental with a native that feeds birds. Add trees to a churchyard, a park edge, or a business frontage. Advocate for street trees on a hot block. Volunteer for a community planting day. Apply for a grant. Encourage a homeowners association or a municipality to adopt tree-friendly policies. Record every tree in the statewide tracker so that your effort counts and inspires others.

The Tree for Every Delawarean Initiative exists to make these actions easier, more effective, and more connected. Homegrown National Park exists to make them part of daily life. Together, they can turn a landscape of lawns into living networks of native canopy that serve people and wildlife for generations.

Learn More and Get Involved

Tree for Every Delawarean Initiative – Program Overview and Resources Statewide hub for canopy expansion, grants, technical guidance, and the tree tracker.

https://dnrec.delaware.gov/tedi/

Delaware Forest Service – Urban and Community Forestry

Grants, technical help, and community recognition for towns, neighborhoods, schools, and homeowners associations.

Delaware Forest Service – Main Portal

State forests, forest stewardship for private landowners, forest health updates, and education programs. https://agriculture.delaware.gov/forest-service/

Homegrown National Park – Start Planting Native

Clear homeowner guidance on shrinking lawn, selecting native plants, designing layered plantings, and caring for young trees.

https://homegrownnationalpark.org/get-started-planting-native

Homegrown National Park – Shrink Your Lawn Practical steps to convert turf into habitat and canopy. https://homegrownnationalpark.org/shrink-your-lawn/

Homegrown National Park – Remove Invasive Plants

Identify and replace invasive plants so native trees and shrubs can thrive. https://homegrownnationalpark.org/remove-invasive-plants/

Homegrown National Park – Make a Home for Wildlife

Create habitat at home by providing food, water, shelter, and nesting sites. https://homegrownnationalpark.org/make-a-home-for-wildlife/

United States Department of Agriculture Plant Hardiness Zone Map

Choose trees that will thrive in your location. Delaware is generally Zones 7a to 7b, with coastal moderation in some places.

https://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov

Native Species and Sourcing

Consult Delaware-specific lists of indigenous trees and regional native plant nurseries for restoration- grade stock. Your county conservation district, local garden centers, and the Delaware Forest Service can guide species availability and planting support.

Final Thought

Forests are Delaware’s natural defense system and living heritage. Rebuilding canopy is one of the most effective, equitable, and lasting investments the state can make in public health, climate resilience, biodiversity, and economic vitality. The Tree for Every Delawarean Initiative provides a framework that helps large projects and household plantings add up to something greater than the sum of their parts.

0 Comments